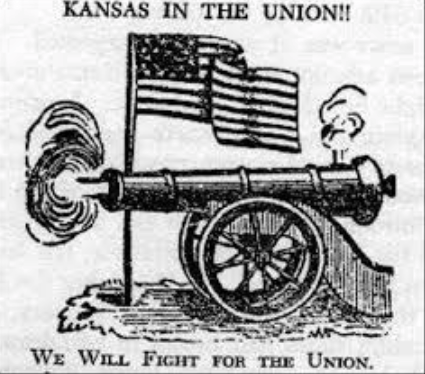

Kansas Joins the Union

Bleeding Kansas To The Union

The winter wind cut sharply across the Kansas prairie, rattling the panes of the small homestead where Thomas Albright sat hunched near the stove. He wore the same frown he’d been carrying for months—ever since talk of Kansas entering the Union as a free state had grown louder.

His younger sister, Margaret, burst through the door with a swirl of snowflakes clinging to her shawl. Her cheeks glowed red, and her eyes gleamed with something Thomas hadn’t seen in a while—hope.

“Thomas,” she said breathlessly. “It’s done. The telegraph rider just came through town. Kansas has been admitted. As a free state.”

Thomas didn’t look up at first. He pressed his palms together, staring at the fire.

“So that’s it,” he muttered. “All this fighting… all this blood… and now Washington decides it for us.”

Margaret stepped closer, lowering her voice. “They didn’t decide it for us. The people did. Free settlers, abolitionists… even the ones who paid in blood at Lawrence and Ossawatomie.”

Thomas clenched his jaw. “You speak as though you weren’t raised by the same father I was.”

“I was,” she replied softly. “But I chose differently. And you know why.”

He did. He could still see the night she helped a runaway man—terrified, frostbitten, barely able to speak—hide in the barn. Their father had been furious, but Thomas had seen the fear in the man’s eyes. It unsettled him more than he ever admitted.

Thomas finally stood and walked to the window. Outside, the neighbors were gathering. Some cheered. Others scowled. Kansas had been torn apart for years—burned towns, skirmishes in the night, ballot boxes stuffed or stolen. Everyone had chosen a side, and now one side had won.

“You think this will stop the fighting?” Thomas asked.

Margaret stepped beside him. “I think this is the beginning of something… maybe something better.”

He shook his head slowly. “Or worse. South Carolina’s already gone. More will follow. This country’s cracking down the middle.”

She placed a gentle hand on his arm. “But you—you still have a choice about the man you’ll be in the days ahead.”

Thomas swallowed hard. He felt the weight of his beliefs shifting—uncomfortably, like boots filled with mud. He didn’t say anything for a long moment.

Outside, a neighbor shouted, “Raise the flag! Kansas is free!”

A cheer erupted. Margaret smiled, tears warming the corners of her eyes. “We’re part of history now, Thomas. Today.”

Thomas exhaled, the sound heavy with years of stubbornness. “Maybe,” he conceded, “history’s got more than one path. Maybe mine’s allowed to change.”

Margaret squeezed his arm. “Then come outside with me. We can disagree—but we can still stand together. This land belongs to both of us.”

He hesitated… then nodded.

As they stepped out into the cold, the prairie seemed different—brighter, almost—though the war that loomed ahead hung over them like gathering clouds. Still, in that moment, the siblings walked side by side, the wind carrying both relief and uncertainty across the newly-minted free state of Kansas.

It was a beginning.

And the beginning was enough.

The winter wind cut sharply across the Kansas prairie, rattling the panes of the small homestead where Thomas Albright sat hunched near the stove. He wore the same frown he’d been carrying for months—ever since talk of Kansas entering the Union as a free state had grown louder.

His younger sister, Margaret, burst through the door with a swirl of snowflakes clinging to her shawl. Her cheeks glowed red, and her eyes gleamed with something Thomas hadn’t seen in a while—hope.

“Thomas,” she said breathlessly. “It’s done. The telegraph rider just came through town. Kansas has been admitted. As a free state.”

Thomas didn’t look up at first. He pressed his palms together, staring at the fire.

“So that’s it,” he muttered. “All this fighting… all this blood… and now Washington decides it for us.”

Margaret stepped closer, lowering her voice. “They didn’t decide it for us. The people did. Free settlers, abolitionists… even the ones who paid in blood at Lawrence and Ossawatomie.”

Thomas clenched his jaw. “You speak as though you weren’t raised by the same father I was.”

“I was,” she replied softly. “But I chose differently. And you know why.”

He did. He could still see the night she helped a runaway man—terrified, frostbitten, barely able to speak—hide in the barn. Their father had been furious, but Thomas had seen the fear in the man’s eyes. It unsettled him more than he ever admitted.

Thomas finally stood and walked to the window. Outside, the neighbors were gathering. Some cheered. Others scowled. Kansas had been torn apart for years—burned towns, skirmishes in the night, ballot boxes stuffed or stolen. Everyone had chosen a side, and now one side had won.

“You think this will stop the fighting?” Thomas asked.

Margaret stepped beside him. “I think this is the beginning of something… maybe something better.”

He shook his head slowly. “Or worse. South Carolina’s already gone. More will follow. This country’s cracking down the middle.”

She placed a gentle hand on his arm. “But you—you still have a choice about the man you’ll be in the days ahead.”

Thomas swallowed hard. He felt the weight of his beliefs shifting—uncomfortably, like boots filled with mud. He didn’t say anything for a long moment.

Outside, a neighbor shouted, “Raise the flag! Kansas is free!”

A cheer erupted. Margaret smiled, tears warming the corners of her eyes. “We’re part of history now, Thomas. Today.”

Thomas exhaled, the sound heavy with years of stubbornness. “Maybe,” he conceded, “history’s got more than one path. Maybe mine’s allowed to change.”

Margaret squeezed his arm. “Then come outside with me. We can disagree—but we can still stand together. This land belongs to both of us.”

He hesitated… then nodded.

As they stepped out into the cold, the prairie seemed different—brighter, almost—though the war that loomed ahead hung over them like gathering clouds. Still, in that moment, the siblings walked side by side, the wind carrying both relief and uncertainty across the newly-minted free state of Kansas.

It was a beginning.

And the beginning was enough.

The town of Leavenworth, one of the earliest organized free-state strongholds, buzzed with a mix of disbelief and vindication as word of statehood spread. Riders had galloped from the telegraph office, carrying the message that after six years of strife, constitutional conventions, and national debates, the long-tormented Kansas Territory had finally been admitted—not under the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, but under the anti-slavery, free-state Wyandotte Constitution.

By midday, people poured into the square—farmers, merchants, freedmen who had cautiously settled near the Missouri border, and veterans of the Free-State militias who had fought to keep Kansas from falling under pro-slavery control.

Thomas and Margaret reached town just as a young man stood on a wagon bed reading a freshly arrived newspaper. His voice carried over the wind:

“‘January 29, 1861: President James Buchanan signs the act admitting Kansas into the Union as a free state.’”

A rumble passed through the crowd. Some shouted with joy. Others—mainly emigrants who had moved from Missouri with pro-slavery hopes—stood stiff-jawed, wounded by the outcome.

Thomas recognized one of them: Caleb Morgan, who had fought at the Wakarusa War standoff in 1855 and had helped blockade free-state settlers.

Caleb strode forward. “You hear it, Tom? After everything—we lost. Folks died for this ground. Sheriffs, settlers, Missourians crossed the border by the hundreds to hold this territory. And now Washington strips it from us.”

Thomas inhaled slowly, remembering the violent months when ruffians poured across the Missouri line to cast fraudulent ballots, when the free-state town of Lawrence was sacked and its presses thrown into the street.

“We all sacrificed,” Thomas replied quietly. “But maybe this—this end—prevents worse.”

“Worse is coming,” Caleb snapped. “South Carolina seceded last month. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama—gone. With Kansas lost, the South will fight harder.”

He stormed off, disappearing into a cluster of disgruntled settlers.

Margaret watched him leave. “He’s clinging to a world that’s slipping away.”

Thomas sighed. “For years, this land was a battleground. Men from the East came to make it free. Men from the South came to make it slave. And folks like me… I don’t even know anymore. We were all swept up in it.”

A group of free-staters began raising a new flag—one they had sewn themselves with a 34th star stitched hurriedly into the blue field. As it rose, cheers erupted, mixing with the hum of conversations about what this meant for the fractured nation.

A schoolteacher near the fire explained the significance to her students:

“This is the triumph of the Wyandotte Constitution. After the fraudulent Lecompton Constitution was rejected—after Congress refused to let slavery be forced upon Kansas—the people’s voice finally prevailed.”

Thomas listened in silence. He remembered the Lecompton Constitution well—how its passage had nearly torn the territory into open war, how President Buchanan supported it while Senator Stephen Douglas fought bitterly against it, claiming it violated the principle of popular sovereignty.

“That document nearly destroyed us,” Margaret murmured, echoing his thoughts. “Kansas became the nation’s proving ground—its fracture line.”

As the fire warmed the crowd, old debates resurfaced, not with anger this time, but with reflection:

• How abolitionists like John Brown had taken up arms, convinced that slavery could only be resisted with force.

• How towns like Lawrence had endured raids and burnings.

• How the federal government had hesitated, faltered, and often fueled division.

• How the question of Kansas had helped split the Democratic Party in 1860, paving the way for Lincoln’s election.

“Maybe Kansas becoming free,” someone said, “was always meant to be the spark. Now the whole country has to reckon with the path it’s taken.”

Thomas felt a chill—part cold, part truth.

As dusk fell, Margaret and Thomas started home past the frozen fields where militias had once trained and where border ruffians had ridden through the night. The land looked peaceful now, deceptively so.

“You think this brings peace?” Margaret asked quietly.

Thomas shook his head. “No. But it ends one chapter. And that’s something.”

He paused. “The war’s coming, Margaret. Everyone knows it.”

“Then let Kansas be remembered as a line drawn for the better,” she replied.

For the first time, Thomas allowed himself to think that maybe his father’s beliefs didn’t have to chain him to the past. Kansas had been forced to choose—and now he could choose too.

As the first stars appeared over the prairie, Kansas breathed its first full evening as a free state—still wounded, still divided, but finally certain of what it stood for.

And Thomas Albright, walking beside his sister, realized that history had moved forward—

and he had taken his first step with it.

Historical Synopsis

The path to Kansas statehood was one of the most violent and politically significant struggles in pre–Civil War America. Following the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the territory was opened to settlement under the principle of popular sovereignty, allowing residents to decide whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. This immediately drew pro-slavery settlers from Missouri and free-state supporters from the North, resulting in fraudulent elections, competing territorial governments, and widespread violence known as Bleeding Kansas.

Between 1855 and 1858, four separate constitutions were drafted in an attempt to establish lawful government. The most controversial, the Lecompton Constitution (1857), attempted to admit Kansas as a slave state despite evidence of election fraud. It was supported by President James Buchanan but fiercely opposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas and the majority of Kansas settlers. After national debate, Congress rejected the Lecompton Constitution. In 1859, free-state delegates drafted the Wyandotte Constitution, solidifying Kansas as a future free state.

As Southern states began seceding following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, congressional opposition to Kansas’s admission weakened. On January 29, 1861, President Buchanan signed the act admitting Kansas to the Union as a free state, ending years of territorial conflict. Kansas’s entry shifted the political balance further in favor of the Union as the Civil War approached, symbolizing the triumph of free-state principles in the territories and marking one of the final political battles before open conflict erupted.

This story is based on documented historical records and contemporaneous accounts

Works Cited

“An Act for the Admission of Kansas into the Union.” 36th Congress, 2nd Session. 29 Jan. 1861. U.S. Government Printing Office.

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford UP, 1988.

Malin, James C. The Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Birth of the Republican Party, 1854–1861. University of Kansas Press, 1959.

Senate Historical Office. The Kansas Statehood Debate, 1854–1861. U.S. Senate Historical Office, 2020.