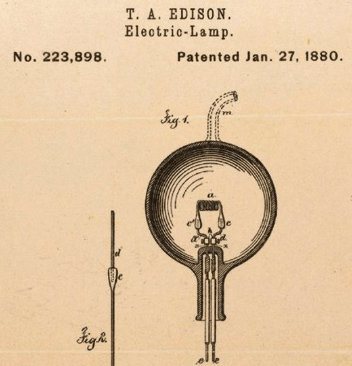

Thomas Edison Light Bulb Patent

A Patent For Light

The winter wind rattled the thin windowpanes of the Menlo Park laboratory, but inside the room glowed warm with lamplight—Edison's lamplight. The prototype bulbs hanging from the rafters gave off a steady amber shine, their filaments humming faintly like violin strings.

Thomas Edison stood hunched over his cluttered workbench, ink-stained fingers tapping impatiently on a stack of documents. Around him, his core team—Charles Batchelor, Francis Upton, and John Kruesi—sorted through wires, glass globes, and sheets of calculations.

A telegraph runner burst through the door, breathless.

“Mr. Edison! Sir—this just came in from Washington!”

Edison spun around so quickly his spectacles slipped down his nose. “Let me see it.” He snatched the envelope, tore it open, and a slow grin stretched across his face.

Batchelor leaned in. “Is that—?”

“It is,” Edison said, holding the paper up toward the faint glow of the bulb overhead. “Patent No. 223,898. The United States government has officially recognized our incandescent lamp.”

A chorus of relieved laughter filled the room. Kruesi let out a whoop loud enough to shake the rafters.

“Well, Tom,” he said, wiping his forehead, “we’ve spent nights here eating cold beans and inhaling enough carbon to blacken our lungs. Good to know it paid off.”

Edison chuckled. “We didn’t work for comfort, John. We worked for a revolution.”

Upton stepped forward, eyes bright. “Sir, do you think cities will adopt it quickly? Electric light in every street? Every building?”

Edison placed the patent on the table with ceremony. “Mark my words, Francis—very soon, gaslight will be as old-fashioned as whale oil. The future will glow at the flick of a switch.”

Batchelor crossed his arms. “But there’s the matter of convincing the public. Many still think electricity is dangerous—some think it’s witchcraft.”

Edison’s eyes sparkled behind his glasses. “Then we’ll show them,” he said. “Do you remember how the neighbors stood outside last Christmas Eve, gawking at the lights burning all night in the window? They thought it was magic then, too. It wasn’t magic—it was persistence.”

Upton glanced up at the quietly burning bulbs. “How long did that one last, Tom? Forty hours?”

“Forty-five,” Edison corrected proudly. “And soon I’ll have one lasting fifty. Then a hundred.” He turned to the team. “But today we celebrate. This patent means the world will know our work is sound.”

Just then, another engineer stepped in from the back room, hands smudged with soot. “Mr. Edison, the latest filament test is running hotter than expected. You might want to have a look.”

Edison gave a sharp, excited nod. “Excellent. A patent is just ink on paper—the real victory is what we build next.”

Batchelor laughed. “Tom, the patent arrived twenty seconds ago! You’re already thinking about the next improvement?”

“Of course,” Edison said, grabbing his coat. “We’re not done. This light will change civilization—but only if we keep improving it.”

As he moved toward the test room, he paused at the door and glanced back at his team, a rare softness in his expression.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “today we lit the path to the future. And we’ll keep it lit.”

The men exchanged proud nods. Outside, the winter wind howled, but inside the laboratory, Edison’s bulbs glowed steadily—promising a new age where night could be held at bay by human ingenuity.

And at the center of it all, patent in hand, Thomas Edison walked back into the workshop with the unshakable certainty of a man who knew the world had just changed forever.

Later that afternoon, the team gathered around the long oak table where Edison had spread out maps of major American cities—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago. He tapped them one by one.

“Gaslight limits us,” he said. “It’s dim, expensive, and notoriously explosive. Entire city blocks have burned from a single leak.” He pointed to New York. “With electric light, factories can operate safely at night. That means more production, more jobs, more goods for the country.”

Upton adjusted his spectacles. “It will change education too. Students will be able to read after dark without straining their eyes over flickering lamps.”

Batchelor added, “And hospitals—patients won’t be treated in shadows anymore. Surgeons will have steady light. Lives will be saved.”

Edison nodded firmly. “This is about progress. America is rising—railroads, telegraphs, booming cities. But every great leap forward has been slowed by one thing: darkness. Once we conquer the night, industry will expand in ways we can’t even predict.”

Kruesi leaned back, marveling. “Imagine a fully electrified city. Streetcars running after dusk, shops lit well into evening, people walking safely without carrying lanterns.”

“And farms,” Upton chimed in. “Electric pumps, refrigeration, lighting for early-morning chores. It could transform rural life as well.”

Edison looked around at his men, his voice lowering.

“Gentlemen, this lamp is not just a device—it is the foundation of an electrical system. Power stations, wiring networks, generators. Within a decade, America could become the world leader in electrical infrastructure.”

Batchelor smiled knowingly. “You mean to build an empire of light.”

Edison didn’t deny it. “I mean to light the nation. And once the nation is lit, invention will flourish. Workers will stay safer, factories will work faster, and our economy will reach heights we’ve never imagined.”

For a moment, the team fell silent, each man picturing the United States glowing from coast to coast.

“History will remember today,” Edison said quietly. “Not because I earned a patent… but because this patent will help power the century ahead.”

And as the sun set outside Menlo Park, the laboratory remained bright—brighter than any gas lamp could ever hope to be—its steady glow a silent promise of America’s electrified future.

Historical Synopsis

On January 27, 1880, Thomas Alva Edison received U.S. Patent No. 223,898 for his improved incandescent electric lamp. While earlier inventors had experimented with electric lighting, Edison’s design introduced several critical innovations that made widespread, practical use possible. His lamp used a high-resistance carbon filament, a better vacuum, and a configuration that allowed the bulb to burn longer while using less current.

This patent became the foundation of Edison’s larger vision for a complete electrical lighting system. In the months following the patent, he and his team at Menlo Park developed generators, wiring methods, and safety components needed to supply electricity to homes and businesses. Edison’s work ultimately led to the opening of the Pearl Street Station in New York City in 1882, one of the world’s first central power stations.

The incandescent bulb dramatically transformed American society. It enabled factories to operate safely at night, improved living conditions in urban homes, reduced fire risks associated with gas lighting, and accelerated the spread of electrification across the nation. Edison’s patent marked a pivotal moment in the technological modernization of the United States, contributing to its emergence as an industrial and economic leader in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This story is based on documented historical records and contemporaneous accounts

Works Cited

Edison, Thomas A. Electric-Lamp. U.S. Patent No. 223,898, issued 27 Jan. 1880. United States Patent Office.

Friedel, Robert, and Paul Israel. Edison's Electric Light: The Art of Invention. Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Israel, Paul. Edison: A Life of Invention. John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Smith, Merritt Roe. “Edison’s Invention of the Electric Light.” Technology and Culture, vol. 21, no. 1, 1980, pp. 105–124.