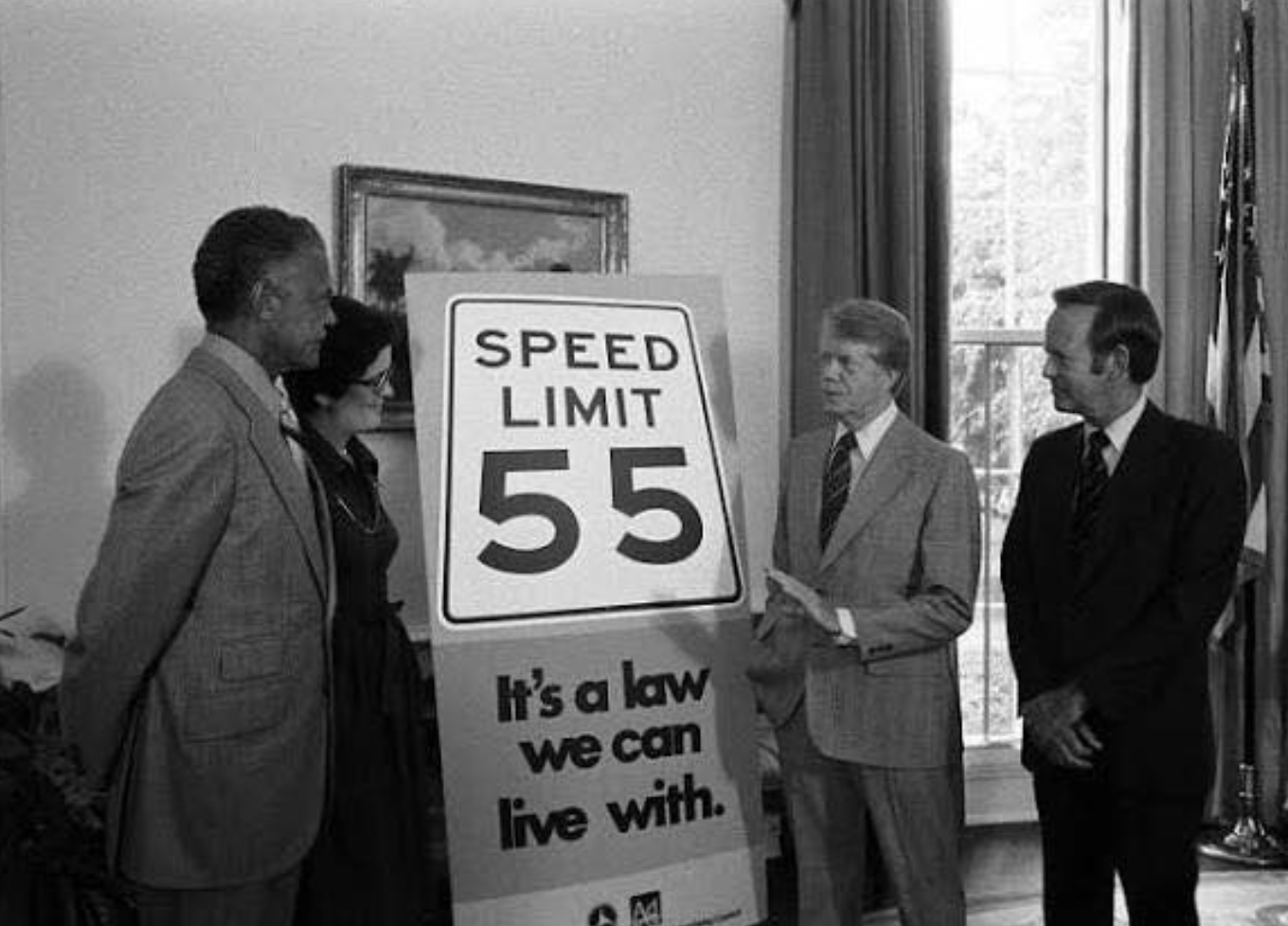

Richard Nixon discussing the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act

Fifty-Five Forever

The sky was still a dull iron-gray when Frank Curtis eased his ’71 Ford Galaxie onto Interstate 80. Dawn hadn’t quite broken, and the Nebraska cold clung to everything—his windshield, his coat collar, even his bones. Frank had driven this stretch for years, first as a soldier returning from Vietnam, then as a long-haul trucker. But this morning the highway felt…different. Restrained. Like the whole country had been placed under a quiet, grinding order.

Ahead of him stood a metal sign so new it still smelled of paint:

SPEED LIMIT 55

NATIONAL MAXIMUM — FEDERAL LAW

Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act of 1974

Frank let his foot ease reluctantly off the accelerator.

“Well, I’ll be,” he muttered. “They really did it.”

The AM radio crackled through the static, replaying President Nixon’s announcement—one that had aired across the nation the night before:

“In order to conserve fuel during this national energy emergency, I have signed legislation establishing a maximum speed limit of fifty-five miles per hour on all interstate highways…”

Frank took a sip of lukewarm coffee from his thermos. Nixon continued, his voice solemn:

“…this measure is expected to reduce gasoline consumption by 2.2 percent. It is a necessary act of national discipline—one I believe Americans will accept as a patriotic sacrifice.”

Frank snorted. “Patriotic? This ain’t drivin’. This is crawlin’.”

Just three months earlier, in October 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries—OPEC—had tightened their grip on the world’s oil supply. In retaliation for U.S. support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War, Arab members of the cartel launched an embargo that rattled every American household. Prices doubled, sometimes tripled. Governors declared states of emergency. Gas stations posted signs reading CLOSED or LIMIT 10 GALLONS. In some states, drivers could only fuel up on odd or even days depending on their license plate number.

Frank remembered those first weeks vividly. Lines so long they wrapped around blocks. Drivers pushing empty Buicks into stations, praying a tanker would arrive. Arguments that turned into fistfights. In the worst moments, police had to be stationed at pumps.

The United States—land of interstate freedom and wide-open roads—had found itself running on fumes.

Frank gripped the steering wheel tighter. His rig didn’t run on patriotism or speeches—it ran on gasoline. And gasoline had become the most precious liquid in America.

“God made the interstates for seventy-five,” he recalled one of his buddies saying back before the crisis hit. “Anything less is un-American.”

But now, under the new law, states that refused to enforce 55 risked losing their federal highway funding. Even Texas, where speed was practically a birthright, had begun pulling down the old 70 and 75 mph signs.

Frank passed a service station on the right—only two pumps active, and a tired attendant hanging a NO GAS UNTIL 3 P.M. placard. It was the same scene everywhere. America was being forced to slow down, whether it liked it or not.

But for Frank, the timing couldn’t be worse.

His daughter Molly lived nearly 500 miles away. She was turning eight today. He had promised—sworn—he’d make it by nightfall with a brand-new red bicycle and a silver bell she had circled three times in the Sears catalog.

Before the new law, he’d have made it comfortably before dinner.

Now? He wasn’t sure he’d make it before she blew out the candles.

At a diner outside Lincoln, Frank stopped for a refill. The waitress, whose apron bore a grease stain shaped almost like America itself, topped off his mug. Behind her, the small black-and-white TV flickered with the morning news.

“Federal officials report that 55-mile-per-hour signs were installed overnight across all fifty states. Supporters argue the reduced speeds will not only save fuel but significantly reduce highway fatalities. Critics insist Washington is overreaching during a time of panic…”

A man in a wool coat grumbled from the counter. “Hell, maybe it’ll save some lives. Lotta folks drive like they’re racing the Soviets.”

Frank raised an eyebrow. He hadn’t considered that angle. The interstate had gotten safer during wartime speed reductions back in ‘42. Maybe history was repeating itself.

Still, the clock was ticking.

The miles dragged on. What used to be a smooth, fast ride now felt like trudging through molasses. His speedometer sat stubbornly at 55. Cars around him did the same—as if the whole nation had been told to breathe slower.

By late evening, Frank finally turned down the familiar street to Molly’s house. His headlights washed over the snow-dusted sidewalk. He parked, stretched his aching back, and grabbed the shiny red bicycle from the trunk.

He knocked.

Molly’s mother opened the door in surprise. “Frank? You actually made it?”

“Barely,” he said, his voice gravelly with exhaustion. “Fifty-five all the way. Took me near twice as long. Government’s idea of saving fuel.”

From the living room, a small voice stirred.

“Daddy?”

Molly sat up on the couch, blanket slipping off her shoulders. Her eyes widened when she saw the bike.

“You’re late,” she whispered.

Frank knelt, brushing her hair gently behind her ear.

“I know, sweet pea,” he said softly. “The whole country had to slow down today. But I didn’t stop. And I got here.”

She wrapped her arms around his neck as tightly as she could.

For the first time all day, Frank didn’t mind going slow.

Historical Synopsis

On January 2, 1974, President Richard Nixon signed the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act in response to the nationwide fuel crisis caused by the 1973 OPEC oil embargo. The embargo had sharply reduced oil supplies, resulting in long gas lines, rationing measures in several states, and rising public concern over America’s dependence on foreign energy.

The Act’s most influential provision created a national maximum speed limit of 55 miles per hour, which was intended to reduce gasoline consumption by increasing vehicle fuel efficiency. To ensure compliance, Congress tied federal highway funding to the adoption of the speed limit, compelling states to enact it even if they opposed federal involvement in local transportation policy.

The law represented a major shift toward federal energy-conservation policy, marking one of the earliest nationwide legislative efforts to reduce fuel usage through behavioral regulation. In the year that followed, traffic fatalities dropped by over 16%. The Department of Transportation released studies proving that slower speeds meant fewer fatal accidents. Fuel savings added up—modest but real. Americans grumbled, but the limit stayed.

By 1977, public support began to fracture. States petitioned for exceptions. By the 1980s, enforcement weakened. Although the 55-mph limit faced criticism for slowing travel and questionable long-term effectiveness, it remained in place until Congress loosened restrictions in 1987 and fully repealed the national mandate in 1995.

This story is based on documented historical records and contemporaneous accounts

Works Cited

Federal Highway Administration. A History of the Federal-Aid Highway Program. U.S. Department of Transportation, 1976.

Nixon, Richard. “Statement on Signing the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act.” Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Richard Nixon, 1974, pp. 3–4.

U.S. Congress. Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act. Public Law 93-239, 2 Jan. 1974.

U.S. Department of Energy. The Energy Crisis and National Policy, 1973–1975. Government Printing Office, 1977.