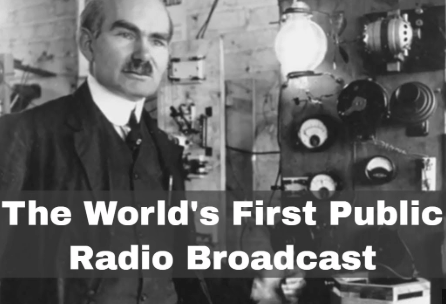

American Inventor Lee de Forest

When America First Heard the Airwaves

Samuel Hartley pressed his gloved hands together as he hurried through the icy New York night. Snow flurries drifted under the streetlamps, glowing like sparks. The city hummed with excitement—rumors had spread across Columbia University that something historic was about to happen at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Samuel adjusted his wire-rim glasses, clutching his battered notebook full of circuits, wave diagrams, and antenna sketches. At nineteen, an engineering major with a mind that raced faster than any telegraph pulse, he felt tonight might be the beginning of everything he dreamed of.

He pushed through the opera doors, joining a small crowd of scientists, journalists, and curious citizens. At the center of the room stood Lee de Forest, sleeves rolled to his elbows, dark hair slightly disheveled, as if ideas were blowing through him like wind.

Samuel stepped closer, heart thumping.

“Dr. de Forest?” he asked.

The inventor turned, eyes bright. “Yes, young man? Are you familiar with radio waves?”

Samuel lit up. “Familiar? Sir, I want to master them. My name is Samuel Hartley—I study engineering at Columbia. I’ve built two receivers in my dorm room. One caught Morse code from a naval ship in the harbor.” He paused, breathless. “But I want to go further. I want people everywhere—every home, every town—to hear the same voice. The same song. From New York to Chicago… maybe even across the ocean someday.”

De Forest studied him for a moment, then smiled. “Then you’ve come on quite the night, Mr. Hartley.”

He gestured toward the equipment: a web of coils, amplifiers, and the experimental Audion tubes Samuel had obsessed over in textbooks.

“I believe we are about to prove that the human voice,” De Forest said softly, “can fly.”

Up in the opera hall, Caruso began to sing—rich, powerful, impossible to contain. De Forest flipped switches, the vacuum tubes warming with a glow.

Samuel leaned forward, barely breathing.

“Is it really happening?” he whispered.

“Listen,” De Forest said.

A faint crackle came through the test receiver nearby—then music. Real music. Caruso’s voice gliding through invisible air, captured by a microphone, amplified by vacuum tubes, carried through the night across miles.

Samuel’s eyes widened. “You… you’ve done it. The first public broadcast!”

A reporter scribbled wildly. A woman gasped and covered her mouth. A technician laughed with disbelief.

De Forest nodded toward Samuel. “No, we’ve done it. This is only the beginning. Someday, Mr. Hartley, engineers like you will do things I can’t even imagine.”

The thought sent a thrill through Samuel’s body.

When the performance ended, the room erupted in applause—even though the true audience was scattered across rooftops, ships, basements, and makeshift receiver stations throughout the city.

Samuel stepped outside into the cold. The city felt different—charged, alive. He stared upward at the dark sky as if he could see sound waves rippling across it.

His roommate Henry ran up, holding a small radio box built from spare parts.

“Sam! I heard it! From our dorm window!” Henry shouted. “Caruso! Actual music! You said it would happen, but I didn’t believe you!”

Samuel laughed, exhaling cold clouds of breath. “Henry, one day people will hear news the moment it happens. Hear presidents speak from thousands of miles away. Hear concerts, weather, stories—everything—without leaving their homes.”

Henry blinked. “You really think it’ll spread that far?”

Samuel’s voice became steady and sure.

“Not just across America. Across the world. No borders. No barriers. Just… connection.”

The snow fell heavier, but Samuel barely noticed. His mind was racing with possibilities—stronger transmitters, coast-to-coast networks, international relays.

Tonight had proven it.

The future wasn’t wired.

It was broadcast.

And Samuel Hartley intended to help build it.

The Impact in the Coming Months

Snow melted into slush as winter loosened its grip on New York City, but Samuel Hartley barely noticed. His world had changed the night Caruso’s voice soared across the airwaves. By February, news of the broadcast had spread far beyond New York.

Newspapers from Boston to St. Louis printed headlines like:

“THE HUMAN VOICE CARRIED BY WIRELESS!”

“NEW ERA OF COMMUNICATION BEGINS.”

Columbia professors quoted the broadcast in their lectures. Engineers debated it over late-night coffee in cramped labs. And Samuel?

He had become a regular visitor in De Forest’s workshop.

One windy afternoon in March, Samuel entered the lab to find De Forest reading a stack of letters.

“Good afternoon, Dr. de Forest,” Samuel said. “What’s all that?”

“Fan mail,” De Forest chuckled. “Mostly from people who claim they heard the broadcast and want to know when the next will be.” He tapped a page. “And this one—listen to this. A man in Connecticut says he built a crude receiver from a cigar box and tin foil and heard the last aria clear as a bell.”

Samuel grinned. “People are experimenting everywhere now.”

“Exactly,” De Forest said. “A spark has been lit.”

By April, colleges across the country had begun forming Wireless Clubs. Samuel received letters from engineering students at Yale, MIT, and even the University of Chicago.

Henry burst into their dorm one night, waving a newspaper.

“Sam! They’re calling it the ‘Broadcasting Craze!’ People are building antennas out of broomsticks!”

Samuel laughed—part pride, part disbelief. But he also felt something deeper:

Responsibility.

The technology wasn’t just exciting anymore.

It was transforming the country.

By May 1910, newspapers had begun asking whether they could send news updates by radio before print deadlines. Editors imagined reading headlines aloud into transmitters so entire cities could hear breaking news in real time.

Samuel overheard a conversation in the lab:

“If we can send opera,” a journalist said, “why not elections? Or weather warnings? Or speeches?”

Samuel’s heart raced.

He wanted that future.

The U.S. Navy, impressed by the clarity of the January broadcast, began visiting De Forest’s lab. Uniformed officers inspected Audion tubes and peppered Samuel with questions about signal range.

One officer leaned in and whispered to him:

“Son, if we can send music, we can send distress calls. Instructions. Entire commands. You boys might save lives.”

Samuel nodded, suddenly aware of the stakes.

In June, De Forest entrusted Samuel and a small team with an ambitious project:

“Let’s try to broadcast from New York to Philadelphia.”

Samuel stared at him. “Sir… that’s nearly 100 miles.”

De Forest smiled. “Then we’d better get to work.”

For weeks, Samuel worked late into the night—adjusting coils, testing antennas, sketching wave patterns in chalk until his hands were black with dust. Henry brought him sandwiches, reminding him to sleep. He rarely listened.

The attempt was made on June 28th.

The signal crackled… wavered… and—

A faint voice reached the Philadelphia receiving station.

Not perfect.

But possible.

Samuel felt electricity surge through him—not from the equipment, but from the realization:

Distance was no longer a boundary.

By August 1910, America was buzzing—quite literally—with the idea of wireless voice transmission.

Families crowded around Makeshift receivers.

Students built antennas from their roofs.

Tinkerers in barns experimented with coils and crystal detectors.

Samuel stood on the steps of Columbia one warm evening as a group of students argued animatedly:

“We could broadcast baseball games!”

“No—political debates!”

“Imagine hearing the President speak live!”

Samuel smiled.

This was exactly what he had dreamed of on that snowy January night.

De Forest joined him on the steps.

“You see what you’re a part of, Samuel?” he said.

“Something bigger than I imagined,” Samuel replied. “Dr. de Forest, people want more. They want news, music, connection. Not just in cities—everywhere.”

De Forest placed a hand on his shoulder.

“Then it’s up to minds like yours to build the network. One transmitter at a time.”

That night, Samuel returned to his dorm window—the same one where Henry had listened to Caruso months earlier.

He looked out at the city lights shimmering like stars, imagining invisible waves passing over them, carrying voices to places they had never reached before.

A whisper escaped him:

“Someday… the whole world.”

The air felt alive with possibility.

And he knew—without hesitation—that he would dedicate his life to expanding this new technology across America and beyond.

The future was already humming.

Samuel would help shape it.

Historical Synopsis

On January 13, 1910, American inventor Lee de Forest conducted the first public wireless radio broadcast in U.S. history from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. Using his newly developed Audion vacuum tube, which amplified electrical signals, de Forest transmitted live performances by opera stars Enrico Caruso and Emmy Destinn to listeners equipped with experimental receivers across the city. This event marked the first time that human voices and music—rather than Morse code—were sent wirelessly to a broad public audience. Although the audio quality was inconsistent, the broadcast represented a revolutionary step in communication technology. It demonstrated the feasibility of mass electronic broadcasting and laid the foundation for modern radio, television, and wireless communication. In the months that followed, newspapers widely reported the event, inspiring universities, engineers, and amateur enthusiasts to begin radio experimentation, and solidifying the United States as an early leader in the development of broadcast media.

This story is based on documented historical records and contemporaneous accounts

Works Cited

De Forest, Lee. Father of Radio: The Autobiography of Lee de Forest. Wilcox & Follett, 1950.

Douglas, Susan J. Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899–1922. Johns Hopkins UP, 1987.

Hilmes, Michele. Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922–1952. U of Minnesota P, 1997.

“Wireless Telegraphy: De Forest Sends Opera Through the Air.” The New York Times, 14 Jan. 1910, p. 1.