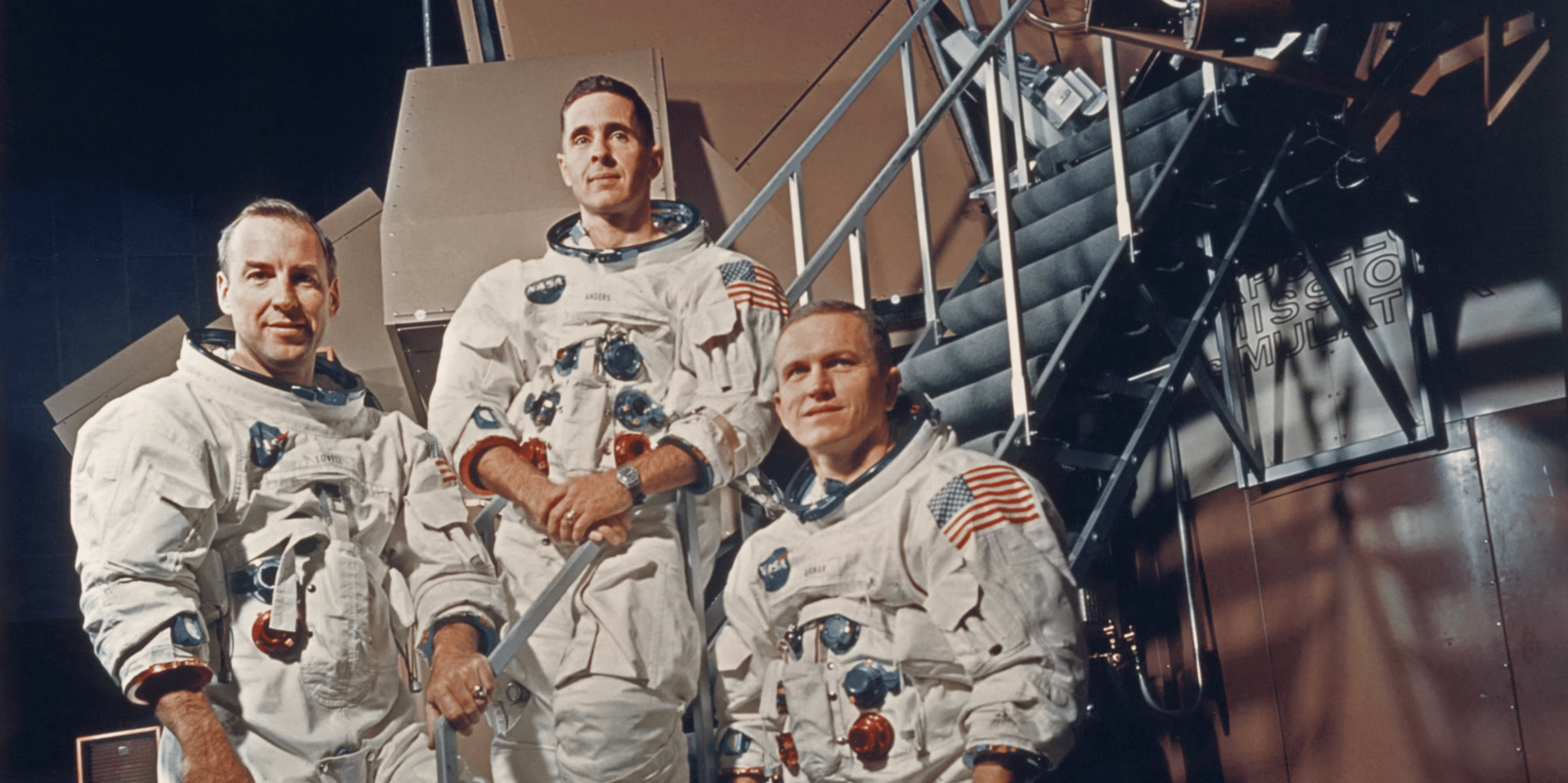

The Crew of Apollo 8—Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders

Earthrise on Christmas Eve

The Moon filled the window like a silent witness.

William Anders floated closer, steadying himself with one hand on the console. For days now, everything outside had been either darkness or blinding gray rock. Beautiful, yes—but distant. Unreachable. Untouchable.

Then it happened.

“Oh my God,” Anders said softly.

Jim Lovell turned from his checklist. “What is it?”

Anders didn’t answer right away. He was staring out the window, heart pounding. Rising slowly above the lunar horizon was something impossibly familiar—blue and white, wrapped in cloud and light.

“Look at that,” Anders finally said. “There’s the Earth.”

Frank Borman pushed himself over. “That’s home.”

For a moment, no one spoke. The spacecraft hummed quietly, doing exactly what it had been designed to do, while three men stared at a fragile sphere hanging in the void.

Anders reached for his camera.

“Don’t lose it,” Lovell joked, breaking the spell just enough to breathe again.

“I won’t,” Anders replied. His voice was steady, but his hands trembled as he framed the shot. He adjusted, clicked, then clicked again. Color film. He knew instinctively this mattered—that black and white wouldn’t be enough.

“There,” Anders said. “We finally have something worth sending back.”

Borman smiled. “On Christmas Eve, no less.”

Anders nodded. Billions of people were preparing for dinner, for church, for family. And here he was, farther from Earth than any human had ever been, holding proof that the planet was not endless or invincible—but small. Finite. Alone.

He looked again, this time without the camera.

“All our arguments,” he said quietly. “All our borders. Wars. Politics.” He shook his head. “None of it shows up from here.”

Lovell followed his gaze. “Just one world.”

“One world,” Anders repeated. “And we’re sitting out here risking everything… to look back at it.”

The realization settled into him—not as fear, but responsibility. If Earth could look that delicate from the Moon, then it was that delicate. And people needed to see it.

“They’ll understand,” Anders said, more to himself than the others. “Once they see this… it’ll change how they think.”

Borman glanced at the clock. “We’re live in a few minutes.”

Anders took a final look before pushing away from the window. “Good,” he said. “Let’s remind them what they’ve got.”

When the broadcast light flicked on, Anders knew the photograph was already on its way home—carrying with it a message no speech could ever deliver:

This is all we have. And it’s worth protecting.

Anders listened as Borman’s voice carried across nearly a quarter million miles of space. The three astronauts took turns reading words written thousands of years earlier—words chosen not for science or strategy, but for meaning.

“In the beginning,” Borman read, “God created the heaven and the earth.”

Lovell continued, his voice steady, reverent.

Anders listened as Genesis unfolded, describing light and darkness, land and sea, creation taking shape out of nothingness. From lunar orbit, the words felt newly literal. He glanced once more at the Earth through the window—a living testament to those ancient lines.

When it was over, Borman spoke again, offering a simple message of peace to a watching world.

Apollo 8 had not been designed to create poetry. It was a rushed mission—born of Cold War pressure, Soviet competition, and a narrow window of technical opportunity. Only months earlier, the spacecraft had never even carried astronauts. Now it was hurtling around the Moon at over 3,600 miles per hour, its crew trusting calculations scribbled on clipboards and faith in engineers back in Houston.

Anders understood the risk intimately. He was not a pilot by instinct like Lovell, nor a commander by temperament like Borman. He was the mission’s eyes—the man responsible for photographing a landscape no one had ever seen firsthand. NASA had tasked him with capturing the Moon in precise detail: craters, shadows, potential landing sites.

Yet the photograph that would define the mission wasn’t on any checklist.

As Mission Control’s voice crackled through the speaker, Anders floated back toward the window one more time. Earth was already slipping out of view again, rotating away as the spacecraft continued its orbit. He felt a sudden urgency—a sense that history had nearly passed him by without warning.

“Houston,” Lovell said into the microphone, “we’re looking at the Earth rising over the Moon.”

Anders watched the planet disappear, then reappear. Blue oceans. White clouds. A thin atmosphere clinging to the surface like breath on glass.

He thought of forests. Rivers. Cities glowing at night. He thought of pollution he’d seen from airplanes, of smog over Los Angeles, of nuclear tests that scarred the land. From here, there were no scars visible—but that didn’t mean they weren’t there.

If anything, that made it worse.

From the Moon, Earth looked defenseless.

As the crew prepared for reentry checks and trajectory calculations, Anders stayed quiet, the image burned into his mind. He knew that once the film was developed, once the image reached newspapers and television screens, it would no longer belong to him.

It would belong to everyone.

Decades later, people would say the space race was about reaching the Moon. Anders would know better. The most important discovery of Apollo 8 wasn’t the Moon at all.

It was the Earth—seen clearly, for the first time, from the outside.

And on Christmas Eve, as billions listened to three voices floating in the darkness of space, one photograph quietly began changing how humanity saw itself.

Historical Synopsis

On December 24, 1968, Apollo 8 became the first crewed spacecraft to successfully orbit the Moon, marking a major milestone in the United States’ space program during the Cold War. Launched by NASA, the mission carried astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders more than 240,000 miles from Earth.

Originally intended as a test of lunar module systems, Apollo 8 was reconfigured in response to intelligence suggesting the Soviet Union might attempt a lunar mission first. The successful journey demonstrated that humans could safely travel to, orbit, and return from the Moon—clearing the path for the Apollo 11 landing the following year.

During lunar orbit on Christmas Eve, the crew transmitted a live television broadcast watched by an estimated one billion people worldwide. As part of the broadcast, the astronauts read passages from the Book of Genesis, offering a message of peace and reflection at the close of a tumultuous year marked by war, assassinations, and social unrest.

That same day, William Anders captured the now-iconic Earthrise photograph, showing Earth rising above the Moon’s horizon. The image profoundly influenced public perception, reinforcing the fragility of the planet and helping inspire the modern environmental movement. Apollo 8 ultimately shifted humanity’s perspective—not only proving technological capability, but redefining how people viewed Earth itself.

This story is based on documented historical records and contemporaneous accounts

Works Cited

Anders, William A., et al. Apollo 8 Mission Report. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1969.

Chaikin, Andrew. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Penguin Books, 2007.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “Apollo 8.” NASA History Office, history.nasa.gov/ap08-abstract.html.